A study by the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie (IZSVe) of two bat colonies in South Tyrol reveals no risk of rabies for humans.

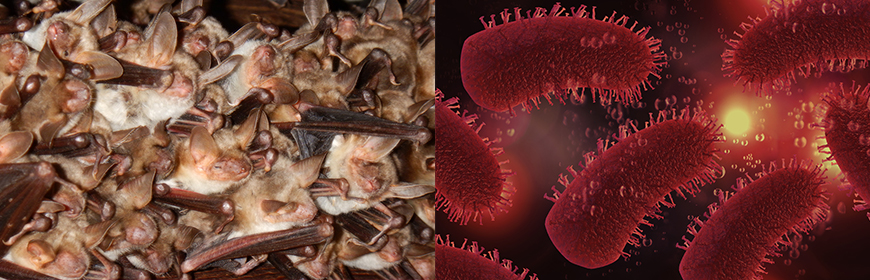

Eight years. That’s how long it took to investigate the transmission dynamics of lyssaviruses in two colonies of two sister species of mouse-eared bats, in South Tyrol, Italy. Researchers from IZSVe’s National Reference Centre (NRC) for Rabies observed that the two colonies, located in buildings used by humans, increased in size to several thousand bats, with numbers doubling after synchronous birthing at the start of the summer. The study was conducted in partnership with the University of Sussex, Imperial College London, the University of Bologna and the STERNA Cooperative of Forlì, and has been published in the scientific journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The colonies, residing in the province of Bolzano, were monitored from 2015 to 2022, at several time points during the mating season of each year, yielding a total of 27 observations. Serological, virological, demographic and ecological data were collected and generated in order to assess the factors underlying European bat lyssavirus 1 (EBLV1) transmission in these animals, in addition to any differences observed over the course of any one mating season, and from year to year.

The lyssaviruses form a family of 17 species of virus, including the rabies virus, most of which are present in chiroptera. However, the EBLV1 virus should not be confused with the rabies virus, which is not currently circulating in Italy. Italy has in fact been clear of rabies since 2013.

The models developed in this study showed that the two colonies experienced seasonal outbreaks driven by various factors.

“Viral transmission in these colonies is initially supported by the presence of individual bats which have poor immune memory at the end of hibernation and roost in large numbers under the roofs of buildings selected by the colony,” explains Paola De Benedictis, Director of the NRC for Rabies and co-author of the article. “Transmission increases exponentially after synchronous birthing since the doubling of colony density (the number of animals in the same space) is also accompanied by the presence of young bats with an immature immune system.”

The researchers have not yet directly found EBLV1 virus, just traces of its passing:

“Despite finding indirect evidence of viral circulation – given the presence of antibodies – no bats have to date tested positive,” continues De Benedictis. “We can therefore assume that transmission of the EBLV1 virus is limited to the bat populations and does not pose an imminent threat to other animals or humans.”

The findings of the study highlight the significant efforts made by the National Reference Centre for Rabies to gain an understanding of the ecological factors underlying pathogen circulation, enabling to more robustly calculate the risk of spillover from reservoir to occasional hosts, including humans. Lyssaviruses can potentially cause rabies in mammals, which is why bats are subject to special surveillance.

“Surveillance and scientific research activities are key to the prevention and control of infectious diseases,” states the General Director, Antonia Ricci. “Over the years, IZSVe, together with the local unit in Bolzano, has implemented numerous collaboration projects with the Veterinary Service of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano and the Veterinary Service of the Health Authority of South Tyrol, oriented around the protection and health of species farmed in the Alpine areas and the conservation of local wildlife.”

Data collection and analysis was supported by funding from the Italian Ministry of Health (WFR GR-2011-023505919, RC IZSVe 08/18 and RC IZSVe 06/19) calls. The collaboration with the British researchers was made possible through ERA-NET ICRAD funding in the framework of the ConVErgence project (BBSRC Grant no. BB/V019945/1).

Read the scientific article in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. »